The LGBTQ movement has never had a neat and clean “origin story.” Our past has been attacked to the point of near erasure over the years, and what is left is often some combination of faded memories, a hand-me-down oral history, or complete fabrication. LGBTQ folks have historically been apprehensive to share their stories, especially in a world so hostile to those who were openly out at the time. It also doesn’t help that our community experienced great losses throughout our community in the 80s and 90s, taking many of those who lived through and experienced the early days of the modern LGBTQ civil rights movement. Many argue that Stonewall wasn’t the beginning of the movement, but really just the breaking point, a culmination of repetitive discrimination spanning decades prior.

The LGBTQ movement has never had a neat and clean “origin story.” Our past has been attacked to the point of near erasure over the years, and what is left is often some combination of faded memories, a hand-me-down oral history, or complete fabrication. LGBTQ folks have historically been apprehensive to share their stories, especially in a world so hostile to those who were openly out at the time. It also doesn’t help that our community experienced great losses throughout our community in the 80s and 90s, taking many of those who lived through and experienced the early days of the modern LGBTQ civil rights movement. Many argue that Stonewall wasn’t the beginning of the movement, but really just the breaking point, a culmination of repetitive discrimination spanning decades prior.

Arguments are made about who threw the first brick or bottle, who broke the police  barricade, or who organized the remaining days of protests and riots. The very people in attendance can’t explain the events exactly as they unfolded, how it escalated so abruptly, or why it happened on that exact night. Some credit revolutionary trans activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera for the uprising, although neither took credit and both denied later in life of initiating any kind of response to the police that fateful night. Some credit Craig Rodwell, owner of the neighborhood Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, for alerting the media and keeping their interest by calling in updates. Some even credit the funeral of performing legend and LGBTQ icon Judy Garland’s funeral occurring the day before as a catalyst. While none of these are definitively the root of the Stonewall Uprising, all of them, to some extent may have played a part. The spark that ignited the rioting and protests to follow may never really be known.

barricade, or who organized the remaining days of protests and riots. The very people in attendance can’t explain the events exactly as they unfolded, how it escalated so abruptly, or why it happened on that exact night. Some credit revolutionary trans activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera for the uprising, although neither took credit and both denied later in life of initiating any kind of response to the police that fateful night. Some credit Craig Rodwell, owner of the neighborhood Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, for alerting the media and keeping their interest by calling in updates. Some even credit the funeral of performing legend and LGBTQ icon Judy Garland’s funeral occurring the day before as a catalyst. While none of these are definitively the root of the Stonewall Uprising, all of them, to some extent may have played a part. The spark that ignited the rioting and protests to follow may never really be known.

Here are some of the facts as we have come to understand them about the Stonewall Inn, and the Stonewall Uprising that are considered the impetus to the following gay liberation movement, and what shaped the LGBTQ civil rights movement we know today. Even these histories listed below can be debated on some level.

- The Stonewall Inn was a small bar in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. The neighborhood was home to those on the fringe of mainstream society, which included many LGBTQ people. The Stonewall Inn was owned by the mafia.

- Police, fire marshalls, health inspectors, and other government officials routinely made rounds to establishments known to be frequented by LGBTQ people. Government officials would often extort the business owners, managers, and patrons for cash payments in exchange for no arrests or not closing the place down. Some officials weren’t interested in extortion, but instead would arrest or write citations. The Stonewall Inn was no exception to this rule.

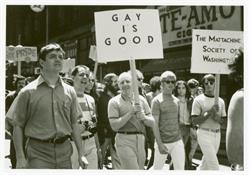

- The cultural narrative of civil liberties, including LGBTQ communities, were slightly shifting. Anti-Vietnam War activism, the civil rights movement, and a general rebellion against mainstream culture (counter-culture) opened doors to talk about more progressive topics like civil rights and equality.

- Like so many times before, the New York City Police entered the Stonewall Inn in the early morning hours of June 28th, 1969. Selectively enforcing statutes, nine policemen arrested employees of the bar, as well as customers for not wearing gender-conforming clothing, and physically harassed other patrons.

- This was the third raid similar to this in an short period of time.

- Police were loading the arrested people from the bar into vehicles as a small crowd formed. The people in this crowd were those who had been cleared from the bar along with individuals from the neighborhood.

- Self-identifying as a black, biracial, butch lesbian, and Drag King, Stormé DeLarverie was struggling against the officers who were trying to arrest her. As they tried to flee, officers hit them in the head with their baton. DeLarverie hit the officer back with a fist, and shouted to the gathering crowd to “do something.”

- More of the crowd began fighting back against the police, and the officers retreated inside of the now empty Stonewall Inn, barricaded themselves in, and called for backup.

- The barricades were breached several times by the now much larger crowd which began to riot in the streets, and the Stonewall Inn was set ablaze.

- Police backup arrived, somewhat cleared the crowd, and then put out the fire.

- Over the following five days, more organized riots and protests persisted. These protests were covered by major media outlets, which brought national attention to many of the names and faces we now recognize as members of Stonewall Uprising’s frontlines. These activists continued to fight for LGBTQ and intersectional civil rights for decades.

- The Stonewall Inn closed after the fire. It was renovated and reopened in 1990.

- In 1993, the Stonewall Inn became the first landmark in New York City to be officially recognized for its importance in LGBTQ history. June of 2016, a National Monument in Christopher Park was dedicated to the movement, and New York State designated the Stonewall Inn as a State Historic Site.

We may never really know exactly what happened that hot summer night in 1969. We may never know who threw the first punch, especially because the ones who were credited denied being the first. One thing that we do know is the past 50 years have seen progress, movement, and a more concerted fight for LGBTQ equality – and for a large part, we owe that to LGBTQ folks who risked arrest, injury, or maybe even death to take a stand against discrimination at Stonewall Inn.

We may never really know exactly what happened that hot summer night in 1969. We may never know who threw the first punch, especially because the ones who were credited denied being the first. One thing that we do know is the past 50 years have seen progress, movement, and a more concerted fight for LGBTQ equality – and for a large part, we owe that to LGBTQ folks who risked arrest, injury, or maybe even death to take a stand against discrimination at Stonewall Inn.

For more information about The Stonewall Uprising and other LGBTQ history, you can visit the archives at the Stonewall National Museum & Archives at stonewall-museum.org.

All photos courtesy New York Public Library